Fundamentalists who try to violently silence cartoonists are one thing, but trying to protect ourselves and others from offensive speech can also harm society.

By Jon Overton

Consider a group of naked protesters who march through a downtown area.

They seek to draw attention to the plight of Bangladeshi and Chinese workers who are paid low wages to manufacture clothes in sweatshops all across southeast Asia.

The sight of so many scantily-clad individuals anywhere in Iowa would undoubtedly horrify or at least astonish many a mild-mannered, Puritanical Midwesterner.

However, if such a protest occurred in Portland or San Francisco, most people probably wouldn’t be too concerned.

This wide difference of opinion highlights why it can be so hard to agree on what counts as offensive. It makes things especially difficult when trying to create laws that restrict offensive speech and expression.

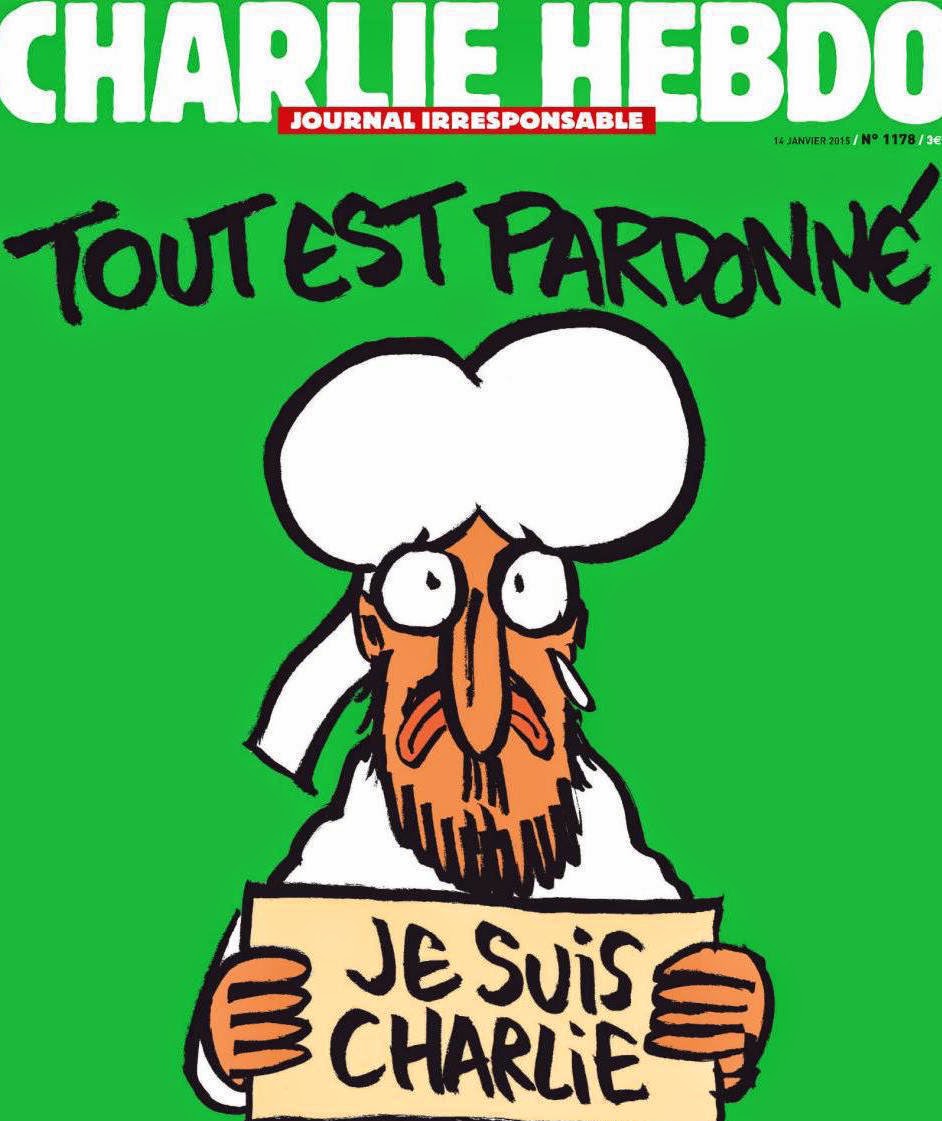

Western society saw the attack on the Paris offices of Charlie Hebdo as an assault on one of its core values: freedom of speech. And it was. The terrorists who shot up the offices of Charlie Hebdo were contemptible bullies.

|

Charlie Hebdo chose this image as its cover for

today's issue. Above the Prophet Mohammad, it

reads, "All is forgiven."

|

It’s easy to identify Muslim fundamentalists as a threat to free speech because for many of us, even those sympathetic to Muslims, Islam is extremely foreign. Strange things are inherently scarier than familiar things.

Freedom of speech is often threatened, yes, by violent fundamentalists, but also by our best intentions to avoid offending others.

The University of Iowa removed an art piece depicting a Klansman covered in newspaper clippings about the history of racial tensions a few hours after it was set up on campus because certain individuals (understandably) were offended.

A University of Kansas professor was suspended after he posted a hostile Tweet about the National Rifle Association.

Last year, Oberlin College recommended that instructors avoid teaching course material that might cause someone suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder to have a flashback if it didn’t directly contribute to the course goals.

The idea in all of these situations was to protect people from offensive speech. But in one way or another, each of these higher education institutions was undermining freedom of speech or at least academic freedom.

Deciding what kind of offensive speech or expression is permissible leads to a huge mess.

Once we start banning certain kinds of speech, it’ll start bringing up questions about what kinds of speech we should legally accept. Any logical progression will lead to a gradual whittling down of what we can say in the name of not offending people.

Consider the aftermath of 9/11. I’ll venture to guess that if you are reading anything from Iowa Peace Network, you opposed the Iraq War from the beginning. Recall that around the start of that war, American protesters were often labeled “un-American” or “unpatriotic.”

This isn’t just a convenient political game. Some people’s sense of identity is based on loyalty to their nation, which had just lost thousands of its citizens and one of its major national landmarks to terrorism. For these individuals especially, questioning the president in wartime could be considered highly offensive, perhaps even worth banning.

And that’s not unprecedented. In 1798, it became illegal to criticize the federal government, supposedly to strengthen national unity. During World War I, Congress passed legislation that made it illegal to say anything negative about the U.S. government or the war effort.

Fortunately, the government ultimately gave up those powers. But do you really want to risk granting such power to today’s ever-expanding surveillance state, which has already scrapped some of our civil liberties behind our backs?

Once you start restricting offensive or hateful speech, it’s not clear where that stops. Free and open discussion and the ability to hold government accountable are too critical in a functioning democracy to risk losing.

So if you’re offended by a giant group of nude protesters, you have every right to respond by voicing your own opinion--perhaps you would brandish banners that read HUMANS ARE MEANT TO BE FULLY CLOTHED AT ALL TIMES. You can respond similarly to anything you find objectionable or with which you disagree. The only thing you can’t do is infringe on other people’s right to be speak their minds.

Jon Overton is the Media Editor of Iowa Peace Network and an undergraduate at the University of Iowa studying Ethics & Public Policy and Sociology.

No comments:

Post a Comment